The Story Behind “The Ballad of Lenora”

Read this post in JP, FR, DE, VI

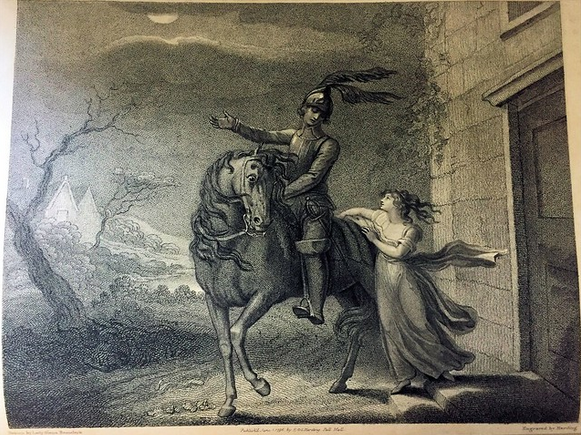

The story behind The Ballad of Lenora, painted by the French artist Horace Vernet in 1839, is a striking testament to how nineteenth-century Romantic painting intertwined with German Gothic literature to portray a tragedy of faith, love, and illusion in the shadow of death.

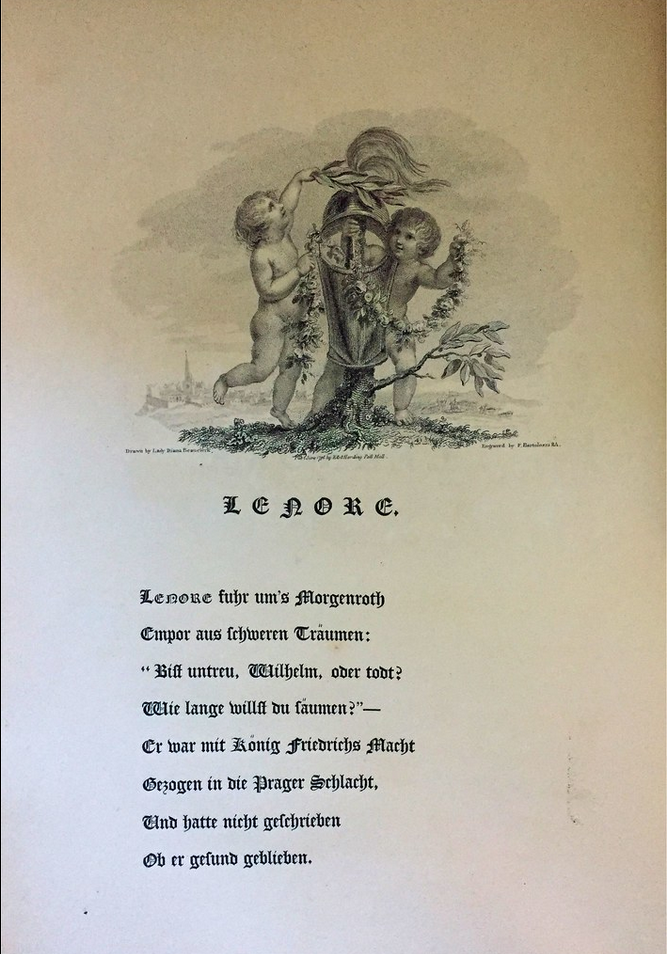

This painting was directly inspired by the poem Lenore (1773) by the German poet Gottfried August Bürger—one of the defining works of the Sturm und Drang movement and a vital precursor to both Romanticism and Gothic literature.

I. The Poem “Lenore” – When Love Crosses the Boundary of Death

The poem unfolds like a dark ballad, filled with elements of:

- War

- Loss

- Shaken faith

- Death personified as a lover

✦ Summary of the story:

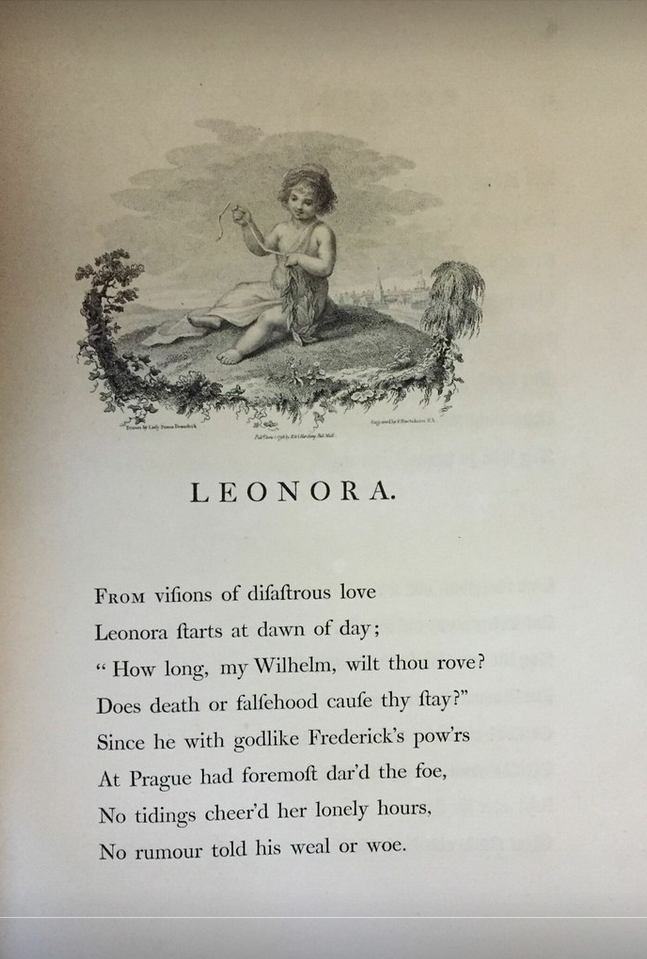

Lenore, a young German woman, waits for her beloved Wilhelm, who has gone to war (likely the Seven Years’ War). When the troops finally return without him, she collapses in despair and cries out against God, asking:

“Where is divine justice, that the good must suffer?”

That night, a horseman appears at her door, claiming to be Wilhelm. He tells her he has come to take her away to their long-awaited wedding—for there is no time to lose.

Without hesitation, Lenore mounts the horse. They gallop through the black of night, passing haunting landscapes and ghostly cemeteries, the wind howling around them. As they ride, the scenery grows colder, more barren, more unreal.

At last, Wilhelm leads her to a graveyard, saying it is the place of their wedding. He vanishes—and before Lenore lies an open grave waiting for her.

II. Horace Vernet’s “The Ballad of Lenora”

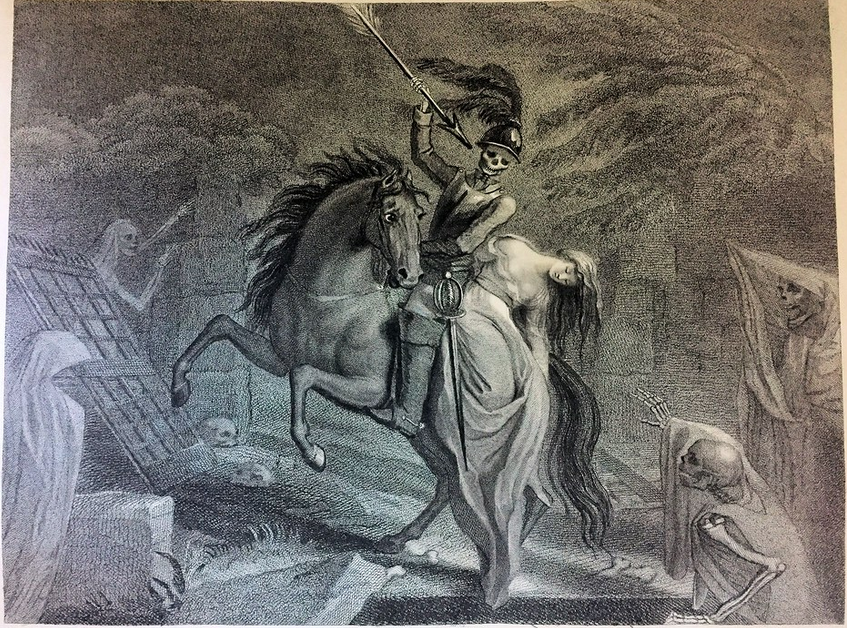

Horace Vernet (1789–1863), best known for his grand depictions of history and battle, turned here to a romantic-supernatural theme, capturing the poem’s most dramatic moment:

Lenore riding through the stormy night with the specter of her dead lover.

The painting evokes:

- A horse racing beneath a thunder-torn sky

- Lenore’s dress and hair whipped by the wind

- Her face caught between awe, terror, and dreamlike surrender

- The rider—cold, expressionless, his features half skeletal beneath the cloak

✦ Symbolic imagery:

- The horse → Time or Death itself — unstoppable, galloping beyond all bounds.

- Lenore → The human soul in despair, lost and vulnerable to illusion.

- Wilhelm / The Rider → Death disguised as love, the fatal embrace from the abyss.

- The landscape → Lenore’s inner world, fogged, chaotic, blurred between life and death.

III. Philosophical and Symbolic Meaning

Beyond its ghostly narrative, the poem and the painting pose profound reflections on:

- ✦ Faith — How one rebels against the divine when love is lost.

- ✦ Love and delusion — Lenore cannot see that death wears the mask of affection.

- ✦ The liminal state (bardo) — the midnight ride as a passage between two realms, life and death, consciousness and the unconscious.

- ✦ Gentle punishment — not by sword or fire, but by falling helplessly into fate’s hands through blindness of heart.

IV. Legacy and Influence in Art

“Lenore” became a model for countless later works:

- Edgar Allan Poe, deeply influenced, echoed its themes in The Raven and Annabel Lee.

- Franz Schubert composed Der Erlkönig, sharing the same “night-ride” motif in which death claims the child.

- In English Gothic literature, the image of the phantom lover and the supernatural wedding night reappears again and again.

A superb "Erlkonig" arrangement for violin and cello [Schubert: Erlkönig] Violinist: Ai Takamatsu x Celloist: Eitosugai

Historical Context

I. Why This Poem Was Written and Why It Resonated

Gottfried August Bürger composed Lenore in 1773, amid an era marked by:

- The aftermath of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) — one of the first truly “global” conflicts, leaving Europe haunted by death and devastation.

- A waning faith in the Church, the State, and the Enlightenment’s Reason, giving rise to Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”)—the precursor to Romanticism.

- A population living in anxiety and grief, bound by moral and religious codes that no longer offered comfort.

Within that suffocating atmosphere, Lenore emerged as a cry of spiritual rebellion:

A woman who dares to rage against God.

One blinded by sorrow, ready to ride with Death itself.

One who chooses love over reason—and is led to her grave as if to a wedding.

The poem shocked its contemporaries—not merely for its supernatural tone, but for its bold engagement with crises of faith, gender, and mortality.

II. Symbolic Meaning – Philosophical and Psychological Depths

1. Lenore as the Image of a Doubting Soul

When she loses her beloved with no explanation, Lenore turns her anger toward God—a blasphemy in her time, yet in truth a voice of honest anguish:

“Why is goodness left undefended?”

“Why must devotion be betrayed?”

Lenore becomes a symbol of the isolated self in an imperfect world, where moral law can no longer make sense of pain.

2. The Horseman as Death – Disguised in the Garb of Love

He does not appear as a reaper, but as a returned lover.

She follows him willingly—and therein lies the poem’s piercing insight:

Death often hides beneath desire.

It is not death itself that terrifies—it is our failure to recognize it.

We ride with illusion, believing we are saved, even as we gallop toward the abyss.

3. The Midnight Ride = The Soul’s Journey Across the Threshold

It is a passage through wakefulness → dream → delusion → death.

The deeper into night they go, the more spectral the scenery—until the grave reveals the truth.

This motif echoes the Bardo of the Tibetan Book of the Dead: a soul drawn by unhealed emotions, choosing the wrong gate in its confusion.

III. Modern Applications – The Lessons of Lenore

✦ 1. Do Not Ride with Illusion

In today’s world, Lenore represents anyone who places blind faith in love, belief, or ambition—without the clarity to discern truth from fantasy.

Whether it’s a lover long gone, a past already dead, or an ideal that has decayed—if we cling to it, it will return in the dark to lead us astray.

✦ 2. Rage Against Faith as the Beginning of Awakening

When Lenore defies God, she is not wicked—she is utterly sincere.

That rebellion marks a sacred stage of growth: a holy doubt, where faith ceases to be a hollow form and becomes something tested by fire.

Like Job in the Bible, or the hermits who wander the mountains, only through doubt can faith be reborn.

✦ 3. What’s Frightening Is Not Death—But Forgetting That We Are Already Dead

Lenore is never forced—she consents.

The lesson is clear: many souls die long before the body, still believing themselves alive, because they keep riding alongside their fears, their past, their illusions.

IV. A Closing Image – The Poetic Moral

There are nights when Death carries no scythe.

He comes whispering, “I will love you forever.”

And she, believing in an unfinished dream, climbs onto the saddle—

…unaware that she is riding toward her own grave.

To truly grasp Lenore not merely as a romantic ghost ballad, but as a living allegory of human psychology,

the following three real or verifiable modern stories will illustrate what it means to be “riding with Death” in our own time.

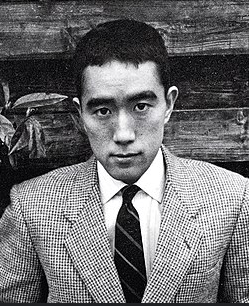

I . The Story of Yukio Mishima – The Rider of a Dead Ideal

Yukio Mishima, the renowned Japanese novelist and activist, exalted the samurai spirit, traditional aesthetics, and a longing to “restore the lost glory” of Japan.

He founded a private militia, the Tatenokai (“Shield Society”), training rigorously in samurai discipline under the ideal of “restoring the Emperor’s sacred authority.”

On November 25, 1970, Mishima mounted his horse one final time—not literally, but through word and deed.

He and his followers stormed the Defense Ministry, seizing the microphone to urge the army to stage a coup and revive “the ancient order.”

No one answered.

Moments later, Mishima committed seppuku—disemboweling himself for a dream that no longer existed.

🕯 Like Lenore, Mishima followed a phantom—

not a lover, but the “pure Japanese spirit” long dead since World War II.

He rode willingly with death, in the name of love for the past, yet abandoned the present, where the world had already moved on.

II. The Story of the Heaven’s Gate Cult (1997)

In 1997 the world was shocked when 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate cult in California committed mass suicide, believing their souls would be “saved” by a spaceship hidden behind the Hale–Bopp comet.

Their leader, Marshall Applewhite, preached that “the body is an obsolete vessel” and that only by leaving it could humans “ascend.”

Wearing identical uniforms, they lay down in orderly rows, swallowed poison, and died in what they believed to be serenity.

🕯 These believers were modern Lenores:

They were not forced.

They wanted to believe—because the real world felt too cruel, too lonely, too empty.

And so they mounted the horse, hoping to reunite with “Wilhelm” in the form of a cosmic ship of salvation.

Their tragedy lay not in evil, but in idealized delusion.

III. A Closer Example – Victims of Toxic Love

Countless people—especially women—remain trapped in abusive, manipulative relationships they cannot escape.

They mistake pain for destiny, believing that if they endure enough, their partner will change.

Tragic cases abound:

- A woman beaten for ten years yet unable to leave, whispering, “I can’t live without him.”

- Teenagers ending their lives after a breakup, believing death proves love.

🕯 These too are Lenores—

when death arrives not with a scythe, but with the promise “I’ll come back,” “everything will be fine.”

They ride with the ghost of love,

journeying toward their own grave—where spirit is drained, trust betrayed, and the inner light fades away.

🔍 Takeaway

✦ In Lenore, death is not always physical. It can be:

- An idea from the past we refuse to release.

- A relationship long decayed that we still clutch.

- A belief never questioned, yet one we ride with every day.

Seen through the lens of psychoanalysis or modern psychology, the story of Lenore is not merely gothic or macabre;

it is a vivid case study of the mind’s extreme mechanisms when confronted with loss, trauma, and the collapse of faith.

I divide it into three analytical layers, so you can see them clearly:

1. Psychoanalysis: Lenore as a Case of the “Thanatos Drive” and the Obsession with the Lost Object

Freud spoke of two fundamental forces: Eros (the life drive, binding and connecting) and Thanatos (the death drive, dissolving and destroying).

When Lenore loses her beloved, Eros loses its anchor—turning into a drive toward death, a form of unconscious self-destruction.

From a psychoanalytic perspective:

- Lenore suffers from object loss — clinging to the ghost of the loved one instead of accepting reality.

- The horseman functions as a transference image: Death assumes the form of the beloved, erasing the boundary between reality and hallucination.

- It mirrors complicated grief or pathological mourning — the inability to internalize the lost person, leading the mourner to pull themselves into darkness to remain “together” with the dead.

2. Modern Psychology: Attachment Disorders and Self-Destructive Behavior

If we read Lenore in the language of the DSM-5, it could be classified as:

- Adjustment Disorder due to Bereavement, or Prolonged Grief Disorder.

- In severe cases: a Brief Psychotic Episode triggered by extreme stress → the apparition of the “rider.”

Phenomena such as Heaven’s Gate, Mishima’s ritual death, or toxic relationships fall along this same spectrum:

→ From loss of faith → loss of grounding → emergence of redemptive hallucination → ritualized self-destruction.

3. The Path Out – How to Stop Riding with Death

✦ a. Recognition

- The first step is to face the loss directly—not deny it, nor keep “riding with the ghost” through fantasy or idealization.

- Accept the anger toward God (like Lenore), but bring it into the light rather than hiding in the dark.

✦ b. Practice “Mourn, Not Merge”

Freud called this the work of mourning (Trauerarbeit): gradually internalizing the lost person as a living memory instead of chasing their shadow.

Psychotherapy, grief-support groups, or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can help rebuild one’s belief system and reduce self-destructive impulses.

✦ c. Build a “Circle of Inner Defense”

Like applying “spiritual insect repellent”:

- Practice mindfulness meditation and breathing to keep daily rhythm.

- Write journals or unsent letters to the lost person as a symbolic release.

- Create a ritual of closure so that the brain can register the loss as complete.

✦ d. If Self-Destruction Becomes a Risk

- Establish a support network—friends, therapists, crisis hotlines.

- Research shows that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) helps grieving individuals rediscover purpose and re-engage with life.

4. Condensed Psychological Lessons from Lenore

- Grief is natural. But clinging to the ghost turns sorrow into self-destruction.

- Doubt and anger toward faith can mark the beginning of awakening—if brought to light instead of followed blindly.

- Build a mental circle of protection before stepping onto the battlefield of each day—just as in your image of the swordsman and the “insect repellent.”

- And when the rider appears—an idea, a person, an illusion—pause and ask:

Is this truly Wilhelm, or Death disguised as him?

Gottfried August Bürger’s Lenore (1773) is not merely a milestone in literary history, but a revelation in the evolution of human consciousness through art.

The poem was a century ahead of its time in depicting that twilight zone of awareness where:

- Faith is no longer absolute,

- Death is no longer an ending,

- And love is no longer salvation—but can become a form of possession.

We can trace Lenore’s footprints across later literature, music, painting, and psychoanalysis.

I will now divide these influential ripples into successive layers of transmission—

a map of how Lenore’s shadow continued to ride through the centuries.

I. Literature – From Early Romanticism to Modern Gothic

✦ 1. The Poem “Lenore” → The Birth of the Modern “Ghost Ballad”

Before Lenore, few works in European poetry dared to unite:

- Human suffering,

- The afterlife,

- And religious rebellion.

After Lenore, an entire lineage of dark, supernatural ballads emerged.

❖ In England:

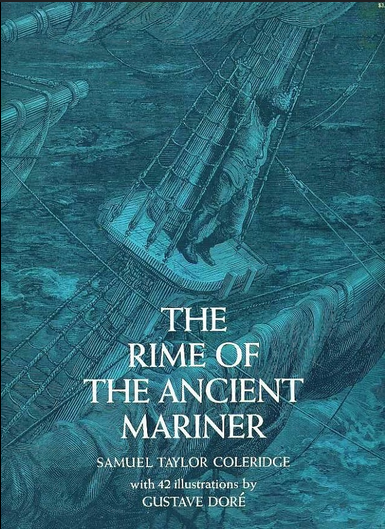

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) — the sailor cursed by the spirit of nature after a crime against life.

- Thomas Gray and Walter Scott expanded the metaphor of the night rider as a symbol of fate and guilt.

❖ In America:

- Edgar Allan Poe was so haunted by Lenore that he wrote his own poem titled Lenore (1843), and repeated the “dead lover” motif in The Raven, Annabel Lee, and Ligeia.

🕯 The woman dies—but her soul lingers in dreams, in midnight knocking, in the black bird’s cry of “Nevermore.”

Thus Lenore is reborn again and again through Poe’s melancholy imagination.

II. Classical Music – Death as a Metaphysical Journey

✦ 2. Franz Schubert – “Der Erlkönig” (The Elf King) (1815)

Based on Goethe’s poem, yet structurally akin to Lenore:

- The night ride,

- The child called by Death,

- The father realizing too late.

🎼 The piece became a cornerstone of German Romanticism, where death is not an ending but a symphonic echo of desire, hallucination, and fate.

✦ 3. Hector Berlioz – “Symphonie Fantastique” (1830)

A musician, betrayed in love, takes opium and dreams of his own execution and of his beloved dancing among ghosts.

🕯 Death + Love + Delirium → the psychological anatomy of a male Lenore.

III. Painting – Giving Form to the Inner Specter

✦ 4. Horace Vernet – “The Ballad of Lenora” (1839)

The very painting we began with: Vernet captures the moment when death is not yet recognized, yet already near.

After Vernet, other painters followed the motif:

- The dead lover on horseback (Delacroix, Fuseli)

- The woman drawn into the underworld by illusion — each a new Lenore for a new century.

IV. Psychology and Modern Popular Culture

✦ 5. Freud & Jung – The Unconscious and the Shadow Lover

Freud never mentioned Lenore directly, yet his description of object-loss neurosis perfectly mirrors her state of mind.

Carl Jung, meanwhile, spoke of the “Shadow Lover”—an image of the anima or animus that appears in dreams: seductive, haunting, and wounding when the psyche fails to integrate it.

Lenore rides with her dead Animus, believing it to be love—when in truth, it is a fragment of her own unhealed psyche.

✦ 6. Popular Culture – Film, Games, and Comics

The motifs of “marriage with death,” “the ghost bride,” “the night ride to the underworld” are everywhere:

- Corpse Bride (Tim Burton) – an animated reincarnation of Lenore.

- Crimson Peak – where a woman lives with the specter of her former husband.

- Bloodborne, Dark Souls – video games rich with Lenore-like imagery:

the woman who dies within a dream, the fallen knight with the lantern.

🧭 Summary – Why Lenore Is the Point of Origin

- It was the first work to fuse three dimensions:

→ Emotional extremity (Sturm)

→ Metaphysical action (the Rider–Death–Wedding of the Dead)

→ The modern spiritual crisis (the collapse of faith) - Lenore thus created a new psychological archetype:

→ No longer “Death coming from outside,” but we inviting Death in, wearing the face we most long to see. - And that is why Lenore still lives, 250 years later—

in every time we love what has already perished,

and in every moment a dead ideal pulls us back toward the grave we mistake for a wedding.

Available in: English · 日本語 · Tiếng Việt · Français