SANDMAN - SILLAGE (FR)

PROLOGUE – SILLAGE

Read this story in EN, DE, VN, JP, HU

****************************

Paris, une nuit de juin 1949

Hôtel Le Meurice – une chambre qui n’a jamais figuré sur le plan.

****************************

The June night wind was not cold enough to shiver,

yet no one wanted to open the window when the room was already burning with the scent of sandalwood, old Armagnac, and the lazy drip of saxophone notes from upstairs.

She stepped in as though she had been here once — in another lifetime.

“Mademoiselle Aimée?”

The concierge’s voice rang from behind — but she did not turn.

She only gave the slightest nod, as though the guest himself had confirmed the identity of the guide.

Inside the room stood only a red velvet chair, a leather-covered table, and a large mirror — that reflected nothing.

And he was already there.

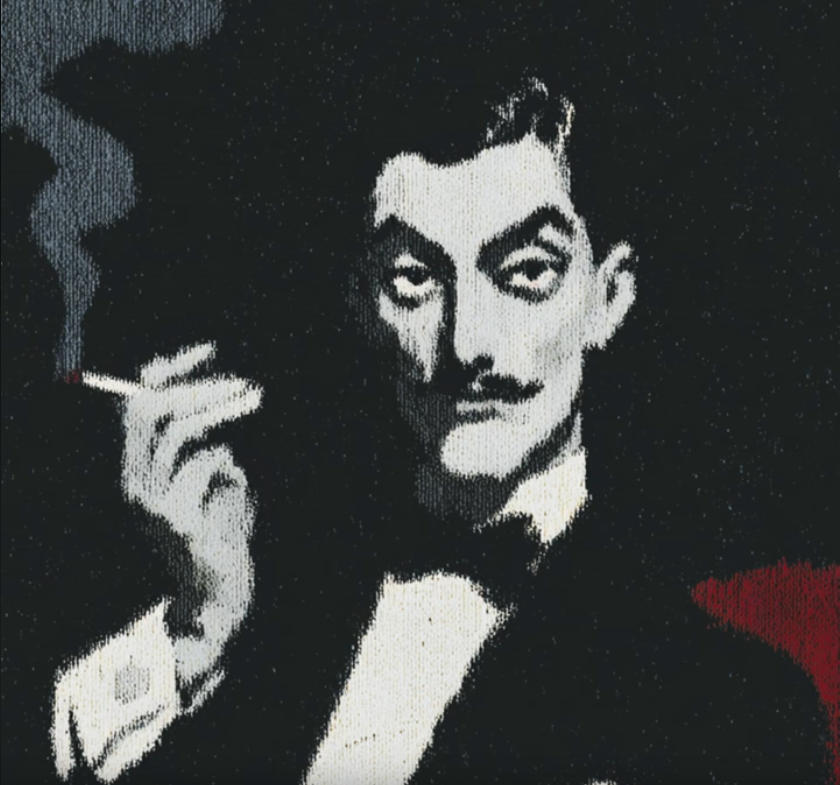

He did not rise. He only watched.

As though waiting for the exact moment to move — not out of courtesy, but for visual effect.

The cigarette smoldered.

His gloved left hand rested on the arm of the chair like a lazy cat.

Nothing made her feel smaller than the fact that he knew her real name — the name only her mother and an old lover had ever whispered.

“I hear you no longer sing.”

His voice — as if he had waited twenty years just to begin with that line.

Aimée said nothing.

She had never told anyone about the night when, after a fever, her voice disappeared —

how she began to dream dreams she could never remember, yet awoke to ink stains on the bedsheets, notes she had not written.

“I want to hear a piece of music I have forgotten.”

Her voice rasped, as if her throat were a wound not yet closed.

He nodded — and turned his chair slightly.

On the table, no score.

No instrument.

Only a small black radio, its dial broken, seemingly connected to nothing at all.

He placed his finger on the tip of the antenna —

and the radio began to sing.

A melody impossible to notate, flowing like smoke through the cracks of memory.

Aimée wept — not because she remembered,

but because for the first time she knew she had once loved someone she had never met.

“I wrote this… but never played it.”

she whispered.

When she looked up, he was gone.

The room returned to normal.

No scent, no song,

and the mirror now reflected only a woman crying —

without knowing why.

From the classified files, French Intelligence Office, 1951:

“The singer Aimée Delacour testified that she ‘met a man in a tuxedo, with languid eyes, who played music from a radio without wires.’

There is no evidence that Room 213 was ever in use.

The music recovered afterwards… matched exactly the handwritten score from 1944 by a Hungarian composer who had died in a concentration camp — never published.”

Who was he?

No one knows.

They only remember one thing:

wherever he appeared, there lingered a faint trail of scent — like a dream still clinging to the wrist of someone who had just fallen asleep.Le vent tiède de juin ne glaçait pas assez pour faire frissonner,

mais personne n’aurait osé ouvrir la fenêtre,

alors que la pièce brûlait déjà d’encens de bois de santal,

de vieil Armagnac,

et des gouttes de saxophone paresseuses tombées d’un étage plus haut.

Elle entra comme si elle y était déjà venue — dans une autre vie.

« Mademoiselle Aimée ? »

La voix du réceptionniste s’éleva derrière elle —

mais elle ne se retourna pas.

Elle hocha simplement la tête,

comme si c’était l’invité qui venait d’attester l’identité de son guide.

Dans la pièce :

seulement un fauteuil de velours rouge,

une table gainée de cuir,

et un grand miroir — qui ne reflétait rien.

Et il était là.

Il ne se leva pas.

Il la regarda simplement.

Comme s’il choisissait le moment de bouger,

non pas par politesse,

mais pour l’impact visuel.

La cigarette brûlait lentement.

Sa main gauche gantée de blanc reposait sur l’accoudoir, comme un chat paresseux.

Rien ne la faisait se sentir plus petite que cela —

sinon le fait qu’il connaissait son vrai nom,

celui que seule sa mère et un ancien amant avaient murmuré.

« J’ai entendu dire que tu ne chantes plus. »

Il parla —

comme un homme qui aurait attendu vingt ans, juste pour commencer par cette phrase.

Aimée ne répondit pas.

Elle n’avait jamais raconté à personne comment,

une nuit, après une fièvre, sa voix s’était volatilisée —

ni ces rêves sans souvenirs,

ces réveils avec des taches d’encre sur les draps,

des notes de musique qu’elle n’avait jamais écrites.

« Je veux entendre un morceau… que j’ai oublié. »

dit-elle.

D’une voix rauque —

comme si sa gorge portait encore la cicatrice d’un cri jamais refermé.

Il hocha la tête —

et fit pivoter doucement le fauteuil.

Sur la table,

pas de partition,

pas d’instrument.

Juste un petit poste radio noir,

bouton cassé,

apparemment non relié à quoi que ce soit.

Il posa son doigt sur l’antenne —

et la radio commença à émettre un son.

Une mélodie impossible à noter,

coulant comme de la fumée à travers les failles de la mémoire.

Aimée éclata en sanglots —

pas de nostalgie,

mais parce que, pour la première fois,

elle comprenait qu’elle avait aimé quelqu’un

qu’elle n’avait jamais rencontré.

« C’est moi qui ai composé ça…

mais je ne l’ai jamais joué. »

murmura-t-elle.

Quand elle releva les yeux —

il était parti.

La pièce était redevenue banale.

Plus d’encens,

plus de musique,

et le miroir reflétait maintenant une femme en larmes —

sans savoir pourquoi.

Extrait du dossier confidentiel – Bureau du renseignement français, 1951 :

“La chanteuse Aimée Delacour affirme avoir ‘rencontré un homme en smoking, au regard flou, faisant jouer de la musique à partir d’une radio non branchée.’

Aucune preuve que la chambre 213 ait jamais été utilisée.

La musique retrouvée par la suite…

correspond mot pour mot à une partition manuscrite de 1944,

jamais publiée, écrite par un compositeur hongrois mort dans un camp.”

Qui était-il ?

Personne ne le sait.

On se souvient seulement d’une chose :

Là où il apparaissait,

il restait toujours une traînée de parfum —

comme un rêve encore accroché au poignet

de celle qui s’était endormie.