Psychoanalysis Series – Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung #1 (EN)

Freud & Jung – The Fateful Companionship

Read this post in JP, FR, DE, VN

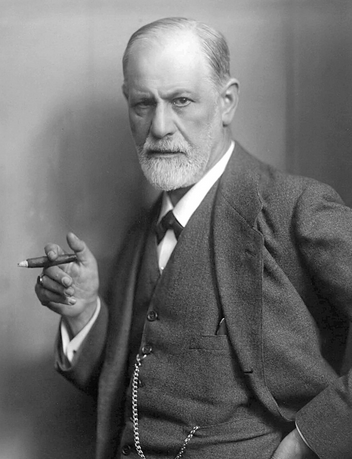

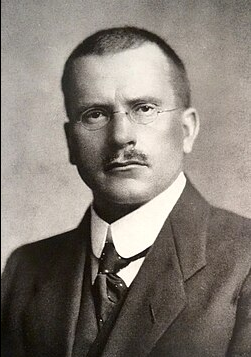

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), the Swiss psychiatrist, and Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the father of psychoanalysis, were two beacons illuminating the dark territories of the human mind.

Their encounter at the dawn of the 20th century marked a pivotal moment in the history of human knowledge.

Freud, with his theory of repressed unconscious drives and the Oedipus complex, opened the door to modern psychology.

Jung, with his mystical sensitivity and introspective temperament, perceived symbols that transcended the limits of medicine: he believed that the unconscious was not merely a prison of memories, but an ocean containing the entire history of humankind — the collective unconscious.

At first, they were mentor and disciple, friends, and kindred spirits. Freud called Jung “the crown prince,” while Jung referred to Freud as “a spiritual father.”

Yet it was precisely their divergence — in their understanding of religion, symbols, and the nature of the unconscious — that eventually drove them apart.

If Freud represented the light of Western rationality, Jung gradually retreated into the spiritual forest of the East — where he no longer sought answers with the scalpel of science, but through symbols, dreams, myths, and ancient wisdom.

Their ideas radiated far beyond psychology.

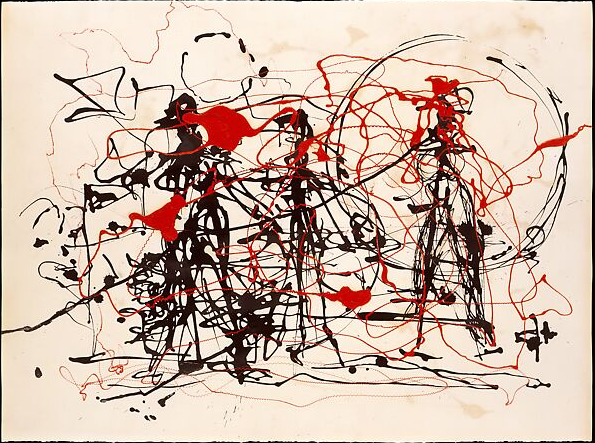

In art: Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and even Jackson Pollock drew from psychoanalytic thought.

In literature: Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Hermann Hesse.

In science: fields such as psychiatry, education, and cultural analysis still bear their imprint.

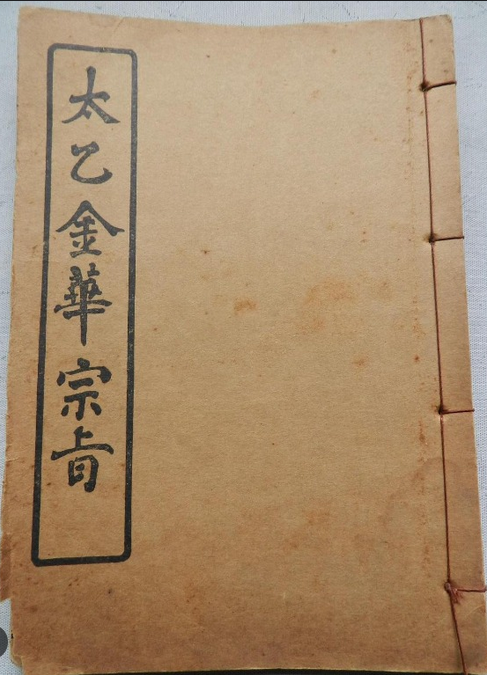

A Letter from the East – The Golden-Lit Door into Darkness

Zurich, winter of 1928.

Snow blanketed the windowpanes. Inside Carl Jung’s study — the space he often called “the cave beneath the unconscious” — the fireplace crackled gently, like the breath of some ancient artifact still alive.

He had just returned from a lecture at the institute — his mind weighed down, tangled in whirlwinds of questions about dreams, the unconscious, and the soul.

It wasn’t that he had no answers. It was that those answers… were no longer enough.

On his desk, among dozens of unfinished manuscripts and mandala sketches, lay a golden envelope — silent, as if it had been there for ages… or had just fallen from another plane of existence.

Jung opened it. The ink was bold, the handwriting precise.

It was from Richard Wilhelm, his kindred friend and Eastern scholar — the man he fondly called “the inner explorer of China.”

“Dear Jung,

I send you a translation never before published. It comes from a deep stratum I believe you will understand — not by logic, but through intuition.

The book is called: The Secret of the Golden Flower (Tai Yi Jin Hua Zong Zhi).

It is not merely a text — but an ancient mirror reflecting the spirit.

Be cautious. And if you lose your way, do not blame me.

– Wilhelm”

Jung looked up. The room swayed in the firelight.

He set the letter down and opened the small book that came with it — ivory cover, faded ink, yet the old Chinese characters glimmered like falling stars from the summit of the sky.

The first line emerged:

“Turn the light around and look within.”

A single sentence — but to him — it rang like an ancient bell deep inside a mountain.

And then, something strange occurred.

The fire seemed to shrink inward, casting his shadow on the wall — but it wasn’t the silhouette of a seated doctor.

It was the shadow of a man in Taoist robes, cross-legged, forming a mudra with both hands.

By his ear, a faint rustle — like pages turning — but not by his own hand.

For the first time, Jung felt he was seeing himself from the other side of the mind — a place Western psychoanalysis had never dared step.

He closed his eyes.

An image bloomed in his inner vision — a golden flower unfolding between his brows, rotating, radiating light.

“The unconscious is no longer a land of repression.

It is a forgotten sacred realm.”

Wilhelm had been right.

This was no ordinary book.

It was an ancient cipher.

Something that — had Freud seen it — might have been dissected under the scalpel of science.

But Jung… Jung had lived long enough in the shadows to know:

There are things that cannot be explained — only lived with.

That night, Jung did not sleep.

He began redrawing the symbols from the book, applying them to his patients’ dreams — and his own.

And mysteriously, everything began to align — like gears long buried in time.

From that day on, Jung was transformed.

He was no longer merely a psychoanalyst —

He became a wanderer of symbols,

a seeker at the gates of forgotten belief systems,

not to believe,

but to understand —

that humanity was never truly separate from the cosmos.

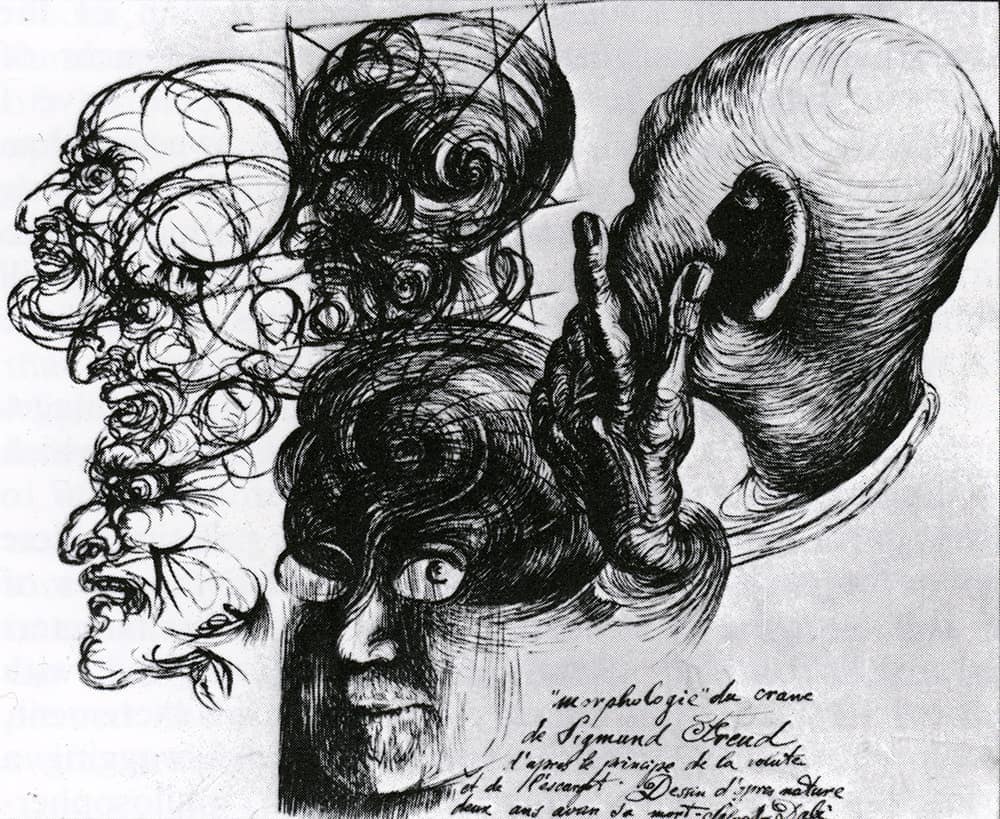

Salvador Dalí and the Melting Clock – The Final Encounter with Freud

London, July 1938.

Maresfield Gardens, a noon heavy with fog — and history.

Inside the modest brick house at number 20, the ticking of an old clock echoed like a warning from a god grown ancient.

Sigmund Freud, 82 years old, having fled Austria as the shadow of the Gestapo crept across Europe, was living out his final days.

Half his jaw had been removed due to cancer.

But his eyes — still the eyes of a man who had once dared to gaze at what others wouldn’t even name: the unconscious.

Suddenly, a knock at the door.

A man stepped in as if he had just emerged from a dream sketched in blood and India ink.

It was Salvador Dalí.

His moustache curled like a fishhook, his rain-spotted coat clinging to him, and his eyes...

they weren’t eyes that looked at the world,

but eyes through which the world seemed to stare back.

He said nothing.

He simply unrolled a sheet of paper and placed an unfinished painting on Freud’s desk:

A human skull — bearing Freud’s visage — unfurling like a spiral.

From the folds of cerebral matter, distorted faces protruded.

Some laughed, some wept, one smoked a cigarette in a breathless wind.

Each expression a level of the mind’s infernal terrain.

Freud didn’t look at Dalí.

He looked only at the painting.

For a long time.

A very long time.

Dalí stood still — like a child before the coffin of a god it once believed to be immortal.

He didn’t breathe. He didn’t blink.

At last, Freud spoke — his voice dry as ash:

“At last, I have met a Spaniard…

whose psyche is truly worth analyzing.”

The words sliced the air like a blade over cold stone.

Dalí didn’t know whether it was praise, a curse — or a final, dissonant note in a symphony about to end.

Freud turned away.

But his shadow — cast long across the wall —

resembled a giant, fractured head

filled with layer upon layer of uncatalogued memory.

Dalí left without saying goodbye.

That night, he dreamed of Freud — transformed into a breathing machine of soft, melting gears, assembling dreams for all humanity.

But the machine faltered.

A rat crawled out from the warped mouth of Freud

and bit through the final thread linking him to reason.

A month later, Dalí completed his painting:

“The Persistence of Memory.”

Clocks melting off stone ledges —

as if consciousness were sliding from the edges of physical reality.

Each second a farewell.

Each minute a spiral of the subconscious.

And every hand of every clock

a needle pricking at Freud’s dreams,

whispering to him:

Not all dreams are to be analyzed.

Some dreams are meant only to... melt.

Freud died a year later.

His housekeeper would later recount:

The clock in his room stopped at 3:15 a.m.

No one could explain it.

Except Dalí —

who, upon hearing the news, smiled

like one who had touched a crack in time

and whispered:

“He didn’t dissolve from death –

He dissolved because, at last,

he became a part of the dreams of others.”

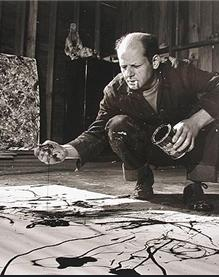

Pollock – A Symphony for the Unspoken Self

New York, 1941.

Rain tapped against the roof like fingers drumming on the skull of a giant.

In a dimly lit room, Jackson Pollock — just past thirty, eyes hollow as if he'd seen hell — sat across from the doctor.

No one spoke.

In the air hung something waiting to be released.

“I can’t speak,” Pollock whispered.

“I have no language for what crawls beneath my skin.

They’re not memories.

Not exactly nightmares.

They… move like snakes.”

The doctor didn’t ask about his mother, or father, or any repressed childhood.

He simply pushed a roll of blank canvas toward Pollock and said:

“Paint.

But not like a painter.

Paint like someone possessed.”

**

That first night, Pollock didn’t sleep.

He poured paint onto the floor.

No brushes.

No frames.

He spun around the canvas like a shaman in trance — barefoot, bloodshot, hands trembling as if summoning spirits from the abyss.

The paint didn’t fall — it leapt.

Each splash tore through order like an electric field unraveling law.

A tangled web of unnamed images emerged —

like the brainwaves of a god convulsing mid-dream.

People asked him:

“What are you painting?”

“I’m not painting,” he said.

“I’m letting the painting… paint me.”

With each session, Pollock shed another layer of skin.

He didn’t know if he was healing — or disintegrating.

One night, he dreamed of running through a maze whose walls were made of black ink, bleeding downward,

chased by the footsteps of a faceless figure in a white coat.

The doctor wrote in his notes:

“Patient Pollock demonstrates an ability to summon archetypal imagery while in a semi-unconscious state.

His paintings are shattered mandalas — the center has collapsed, but the energy remains.

If reason is a city, then Pollock lives in its sewers.”

One final painting left the doctor standing silent for ten full minutes:

A black canvas.

Within it, a single white streak — like a blade — curved, slashed, then shattered.

All around it, red splatters. Blood, perhaps.

Or maybe the suicide of a memory.

When asked what the painting meant, Pollock muttered:

“I think I just saw…

the moment a soul cracked.

And I wanted to freeze that crack

before it turned into a lying word.”

Pollock was never truly healed.

But he was never the same.

After therapy, he walked out like a storm shaped into a man —

a dancer atop the corpses of old definitions:

of art,

of psychology,

of salvation.

No one knows if he conquered his inner demon —

or simply learned to dance with it.

All that’s certain is this:

From then on, every painting by Pollock became an indictment of reason —

and a prayer to the unconscious.